Memories of Joan Baez and Bob Dylan

By Michael Erlewine

Early this morning, in the middle of the night, on ‘YouTube’, I came across a copy of the song “Diamonds & Rust” (1975) written and sung by Joan Baez, and hearing that again, a whole lot of memories came flooding back. Here is the song:

Even today, I can’t hear “Diamonds and Rust” without being deeply moved. Although this song came along some ten-years later than when everything happened, yet the moment it captures was back in those early1960s, for me particularly in the spring of 1961. I will share that.

I can remember sitting around in the ‘MUG’ (Michigan Union Grill) in Ann Arbor, sitting at one of those small gray Formica tables in the first room of the MUG with Joan Baez, having coffee with her, just the two of us. Those were some good times.

Many of the folk artists who came through Ann Arbor back then, people like Bob Dylan, the New Lost City Ramblers, The Country Gentleman, Jack Elliot, and others, stayed wherever we could put them up. However, Joan Baez’s first album was released in 1960, so by 1961 Baez was already getting famous and had money to stay wherever she liked. At that time, the soprano voice of Joan Baez was unlike anything we folkies had ever heard.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s I would hitchhike to New York City often. Back then, unless you had some old junker of a car to borrow, you hitchhiked. Heading out of Ann Arbor, the bad places to get stuck hitchhiking were down by the prison in Dundee, Michigan or trying to get around Toledo, Ohio, that sharp left turn toward the East Coast. Once you got past those areas, it went pretty smoothly, usually. And we would hang in the Village in New York City, sleeping on floors wherever we could. I must have hitchhiked the New York City route some ten times or so.

We were all part of what was called the ‘folk revival’, and all of us were doing what we could to revive the music of rural America and endless ballads and tunes from England and the rest of Europe. Music artists like Joan Baez and Bob Dylan were not writing their own tunes yet, but just helped to restore and protect (revive) whatever went before us.

It would only be a few years there before I segued out of the folk revival mode as I discovered that country and city blues did not need revival, but were alive and well, playing across town, separated by a racial curtain. For this post, let’s talk about what was for me the tail end of the folk revival and my travels to places like Greenwich Village in NYC.

I remember being there with Perry Lederman and Bob Dylan back in June of 1961. Lederman is how I met up with Dylan. They were already friends. Perry Lederman was a phenomenal instrumentalist on the guitar. If Dylan and I were in touch today, we would still marvel at what a player Lederman was.

Lederman played Travis-style, which we used to term “3-finger picking” and his playing was unmatched. Perry Lederman was not a vocalist, and when he did sing it was not special, but he could play like no one I have ever heard. When Lederman took out a guitar, people would listen and marvel. Each song was like hearing a mini-symphony, with an overture, the main theme, variations, and an ending. It was crystal clear and drilled right into your brain.

I traveled with Lederman a number of times and later in 1964 spent time with him during the year I spent in Berkeley, California where both of us were living at the time. After that, I don’t believe I ever saw him again. He died some years ago now and, although there was a CD issued after his death, it was not of his early playing, but something made later and not representative, a shadow of himself, IMO.

Perry Lederman was also an expert at finding and selling old Martin guitars, scavenging them out of attics and garages, fixing them up, and selling them. While traveling with Lederman, I have seen some of the best and rarest old Martin guitars in the world, like double and triple-0 martins with intricate purfling around the edges, rosewood orebony bridges, and intricate inlaid necks and headstocks, sometimes with the Tree-of-Life design.

It would be hard to put a price of any kind on these guitars today. I had one for a while, an old Koa wood Hawaiian guitar. I wonder what I ever did with it. Anyway, back to New York City and the spring of 1961, a time I was hitchhiking with Bob Dylan.

I have memories of Izzy Young, the proprietor of the “Folklore Center” on MacDougal Street in the village. We would hang out there because we had no place else to go and also because that is where you met other players and like minds. Back then, we all smoked all the time, Lederman, me, Dylan, everyone. Cigarettes, caffeine, and some alcohol. That was the thing. Not much alcohol back then.

I don’t know how many days we were in the city on this trip, which was in June of 1961, but it was probably a while. We were hitchhiking and tended to spend at least a day or so at each main stop before moving on, guitars in had.

Plus, Lederman’s mom lived in Brooklyn. I remember visiting her one time and she served us matzo ball soup and I sat at a small kitchen table by a window looking out. I quietly ate my soup while Perry and his mom got caught up. I don’t remember how we got out to Brooklyn or back to the city. It could have been by bus. Hitchhiking in the city was not so good.

What I do remember is one night during that trip being at Gerde’s Folk City on West 4th Street in the West Village with Dylan and Lederman. The three of us were all just hanging out. In those days we stayed up late, usually most of the night. Who knows where we would sleep, but it was not often comfortable, and we were in no hurry for bed.

That particular night, I remember the guitar player Danny Kalb was playing at Gerdes. He was being featured that night or week. Kalb later became part of the group “The Blues Project.”

I am sure Kalb was enjoying his prominence, and I can remember him playing, the lights on him, and Dylan, Lederman, and I standing off toward the shadows. Perhaps it was packed, because I recall walking around in a crowd and there was not a lot of light.

Bob Dylan was not happy about Kalb. I think we all felt that way because Kalb did have an air about him of ‘better than thou’, and who could blame him. He was the man of the hour that night at Gerdes Folk City. That was ‘The’ place.

I can’t remember whether Dylan played a few songs later that night himself or perhaps he or Lederman played some tunes elsewhere. I don’t recall. But I do recall his being irritated by Kalb, and dissing Kalb was not hard to do. As mentioned, Kalb was just a little too full of himself at the time. After all, Gerdes was where all of the folkies wanted to play. And Dylan had played there with the great bluesman John Lee Hooker that previous April.

Thinking back, I don’t think it was jealousy on Dylan’s part with Kalb. Dylan was not petty, as I recall. He was probably just itching to let all of us know he was ‘Bob Dylan’ and wondered why nobody could see this right off. Back then (and it is not so different today), if you had something to sing or had worked on your stuff, you wanted a chance to play and show it off. Dylan was a nervous type and it showed.

Keep in mind that back then Bob Dylan was still trying to find out for himself who he was. This was just before he recorded his first album, that coming fall. I can remember another time, in Ann Arbor, about a year later, when Dylan came to town. He looked me up because we knew each other and I helped him put on a concert at the U-M Michigan Union, and they even spelled his name wrong on the poster. That’s how early this was in his career.

Anyway, the next morning after the concert, Dylan and I were sitting in the MUG (Michigan Union Grill) at one of those little gray Formica tables for hours, drinking coffee and smoking cigarettes while we waited for a review of the concert that Dylan had done the night before as part of the University of Michigan Folk Festival on Sunday April 22, 1962. As mentioned, I am told that I helped make that gig happen. I don’t remember.

Yet I do remember that Dylan was very concerned about how it went over. That is most of what we talked about. He wanted to know how he was received last night. This was before he had the world at his feet.

When the “Michigan Daily,” the student newspaper paper finally came out and we got a copy, sure enough Dylan got a good review. With that he was soon at the edge of Ann Arbor, backpack on, guitar in hand, and hitchhiking to Chicago and the folk scene there. That was perhaps the last I ever saw him.

Back then, there was an established route that folkies like Dylan and me travelled. It went from Cambridge to NYC to Ann Arbor (sometimes to Antioch and Oberlin) to the University of Chicago to Madison and on out to Berkley. It was the folk bloodstream that we all circulated on, either hitchhiking or commandeering some old car for the trip. Most of us hitchhiked.

As mentioned, early folk stars like Joan Baez did not hitchhike, but they still sat around with us in the Michigan Union drinking coffee and smoking cigarettes.

And another time I remember hitchhiking with Bob Dylan and Perry Lederman, heading out of New York City down the road to Boston and on up to “Club 47” in Cambridge. Here was Dylan, standing on the side of the road with a big acoustic guitar strapped around his shoulder, playing, while I stuck out my thumb.

I remember the song “Baby Let Me Follow You Down,” in particular. Even though I did not know at the time that this was the “Bob Dylan” who would become famous, it was still pretty cool. This is the life we all wanted to live back then. We were chasing ‘The Beats’ and reviving folk music.

And Cambridge was another whole city and atmosphere. For some strange reason, I seem to remember the Horn & Hardart automat there and trying to get food from it.

The folk venue “Club 47,” like “The Ark” in Ann Arbor, was one of the premier folk venues in the country, even back then. Today Club 47 is known as ‘Club Passim’ and my daughter, May Erlewine, a well-known singer/songwriter in the Midwest, plays there on her east-coast tours.

Cambridge was where we left Dylan that that trip. He was heading out west hitching along the interstate 90 toward I believe it was Saratoga Springs or perhaps Schenectady, New York for a gig. Perry Lederman and I were hitchhiking on over to New Hampshire and Laconia to attend the annual motorcycle races there, which is another story. I don’t know where we slept at the races. I remember it being just on the ground, but still kind of cold out at night, even in June.

And the motorcycle races were incredible. Large drunken crowds that, when the official races were not being run, would gather and the crowd would part in the middle just enough to allow two motorcycles to race each other, running first gear while the crowd cheered.

The problem was that the crowd pressed in too close and every so often one of the cycles would veer into the crowd and the handlebars would tear into someone’s chest. The ambulances were going non-stop way into the evening. And it seemed the crowd never learned. It was scary and very drunk out. I remember riding on the race track itself on the back of a big Norton motorcycle at almost 100 miles an hour, not something I would do today.

This all took place in mid-June of 1961. The Laconia, New Hampshire races were held from June 15 through the 18th that year. This would put Dylan, Lederman, and me in Gerdes Folk city some days before that.

As to what kind of “person” Bob Dylan was, in all sincerity, he was a person like any of us back then, a player or (in my case) a would-be player. Dylan and I are the same age, born a month or two apart. All of us were properly intense back then. I was 20 years old in 1961. So was Dylan. Imagine!

I vaguely remember Dylan telling me he was going to record an album or had just recorded one; it could have been the Harry Belafonte album where he played harmonica as a sideman on the tune “Midnight Special,” I don’t know. I believe it was later that year that Dylan recorded his first album on Columbia. I don’t remember seeing him much after that, other than later in Ann Arbor.

Something that I got a lot, mostly years ago now, way back then, was the comment that Bob Dylan really can’t sing. I addressed this in an article I wrote years ago, some of which appeared in the biography of jazz-guitar great Grant Green in the book “Grant Green: Rediscovering the Forgotten Genius of Jazz Guitar” by Sharony Andrews (Grant Greens daughter) and published by Backbeat Books. My full article is called “Groove and Blues in Jazz,” which is at this link for those interested, and below is an excerpt:

“Groove and Blues in Jazz”

https://medium.com/@MichaelErlewine/groove-and-blues-in-jazz-efd4b4f31cf1

Here are some notes I wrote about Grant Green: THE Groove Master

“All that I can say about Grant Green is that he is the groove master. Numero uno. He is so deep in the groove that most people have no idea what’s up with him. Players like Stanley Turrentine, Jimmy Smith, Kenny Burrell, and many other really great soul-jazz artists are also groove masters. But the main man is Grant Green. He is so far in the groove that it will take decades for us to bring him out in full. He is just starting to be discovered.

To get your attention and make clear that I am saying something here, consider the singing voice of Bob Dylan. A lot of people used to say the guy can’t sing. But it’s not that simple. He is singing. The problem is that he is singing so far in the future that WE can’t yet hear the music. Other artists can sing his tunes and we can hear that all right. Given enough time… enough years… that gravel-like voice will sound as sweet to our ears as any velvety-toned singer.

Dylan’s voice is all about microtones and inflection. For now, that voice is hidden from our ears in time so tight that there is no room (no time) yet to hear it. Some folks can hear it now. I, for one, can hear the music in his voice. I know many of you can too.

Someday everyone will be able to hear it, because the mind will unfold itself until even Dylan’s voice is exposed for just what it is — a pure music. But by then our idea of music will also have changed. Rap is changing it even now.

Billie Holiday is another voice that is filled with microtones that emerge through time like an ever-blooming flower. You (or I) can’t hear the end or root of her singing, not yet anyway. As we try to listen to Holiday (as we try to grasp that voice), we are knocked out by the deep information there.

We try to absorb it, and before we can get a handle on her voice (if we dare listen!), she entrances us into a delightful dream-like groove, and we are lost to criticism. Instead, we groove on and reflect about this other dream that we have called life. All great musicians do this to us. Shakespeare was the master at this. You can’t read him and remain conscious. He knocks you out with his depth.

Grant Green’s playing at its best is like this too. It is so recursive that instead of taking the obvious outs we are used to hearing, Green instead chooses to reinvest — to go in farther and deepen the groove. He opens up a groove and then opens up a groove and then opens a groove, and so on. He never stops. He opens a groove and then works to widen that groove until we can see into the music, see through the music into ourselves.

Grant Green puts everything back into the groove that he might otherwise get out of it, the opposite of ego. Green knows that the groove is the thing, and that time will see him out and his music will live long. That is what grooves are about and why Grant Green is the groove master.

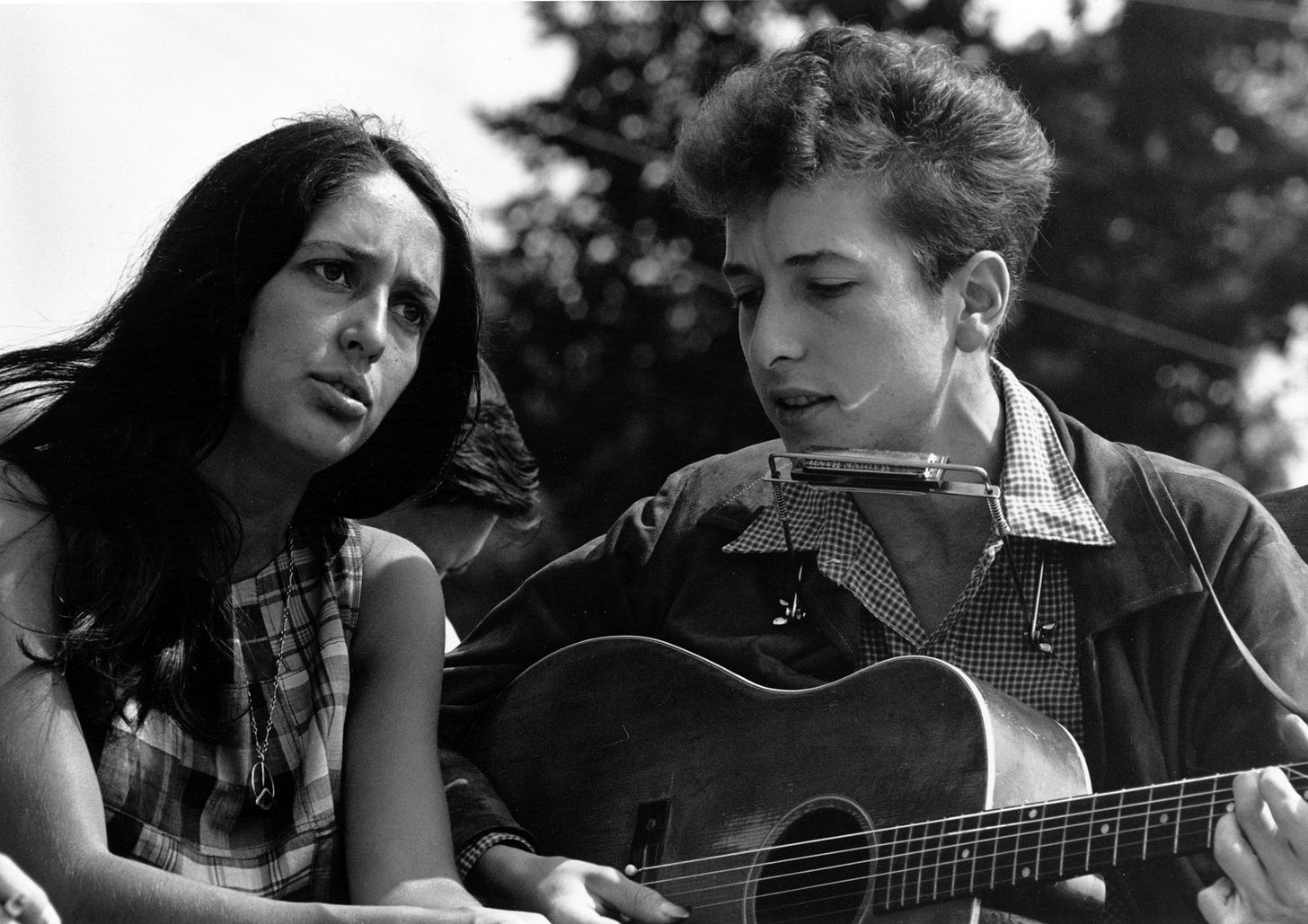

[Photo of Joan Baez and Bob Dylan that is in the public domain.]

EMAIL Michael@Erlewine.net

Note: If you would like to have access to other free books, articles, and videos on these topics, here are the links:

Free books: SpiritGrooves.net

Free Videos:

YouTube.com/channel/UC3cL8v4fkupc9lRtugPkkWQ

MAIN BLOG:

https://www.facebook.com/MichaelErlewine

https://www.instagram.com/erlewinemichael/

https://medium.com/@MichaelErlewine/

http://michaelerlewine.com

As Bodhicitta is so precious,

May those without it now create it,

May those who have it not destroy it,

And may it ever grow and flourish.